Strategy: Porter’s Five Forces + example Uber

Porter's Five Forces is an important strategy concept that helps to explain competitive forces within an industry and how profits are shared among the various participants of it including suppliers, competitors, buyers/customers and substitute products/services. This concept remains equally relevant for traditional firms as well as technology firms.

Porter’s Five Forces is a strategy tool that can help assess the impacts of company internal decisions within the external industry context. It is a tool applied on the main value creating aspects of a firm and not limited to a single department within a firm such as marketing and not even R&D.

Despite its relevance for technology industries, examples often come from traditional industries - a gap that this article will help to close. After explaining the Porter 5 Forces concepts, Part 2 of this article uses Uber as a comprehensive example to demonstrate the value of the 5 Forces for technology industries and firms.

Porter’s Five Forces can be a very useful strategy tool when making important strategic decisions within a firm and even prior to launching on an idea.

This article is structured in 2 parts:

Part 1: Explanation of the 5 Forces concept with a large number of short examples from different industries

Part 2: The in-depth, real-world example of Uber

In the end you will have gained great knowledge on both: the strategy concept as well as Uber (in one important aspect of their business model).

Get all of the below & more to your inbox:

Part 1: Porter's Five Forces

What are the Five Forces (5F)?

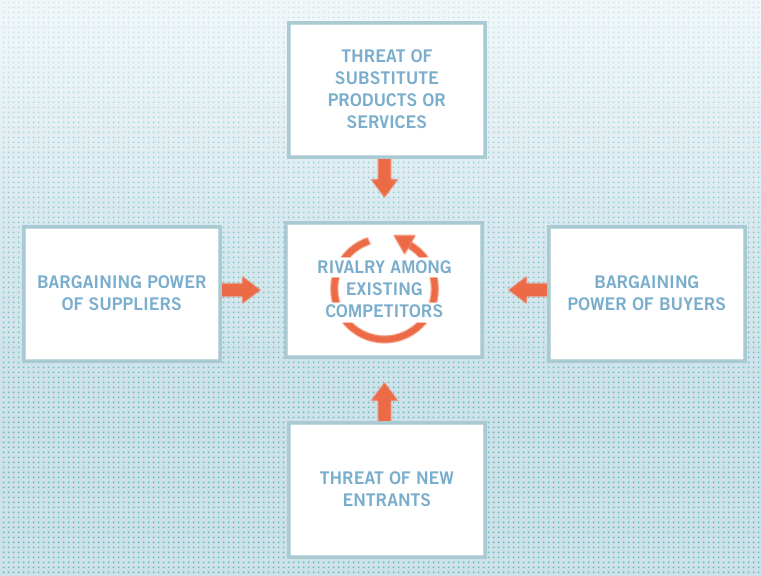

“The Five Forces is a framework for understanding the competitive forces at work in an industry and which drive the way economic value is divided among industry actors” ISC webpages.

Porter's Five Forces [source: ISC webpages]

… and what are the Five Forces (5F) good for?

As an innovator wouldn’t you want to know if you will be profiting from your idea or if someone else (e.g. a key supplier, your distribution channel or your customer) will rapidly capture the majority of the economic benefits of your idea?

According research from Counterpoint, "In Q2 2021, it captured 75% of the overall handset market operating profit and 40% of the revenue despite contributing a relatively moderate 13% to global handset shipments.""

Note that there are considerable quarterly fluctuations to this figure with some quarters even better and others not as good. More importantly, take note that Apple's market share is far higher in the US than globally.

The Five Forces will help to assess & explain:

attractive vs less attractive markets,

identify opportunities and risks,

how profits within an industry are distributed,

extrapolate industry trends & anticipate changing trends.

The Five Forces are:

(1) Bargaining Power of Buyers (=customers)

Where buyers are powerful, profits are generally lower. Buyer power can lead to lower prices or having to increase costs by adding features, services, quantity in order to sell. Where sellers have too much power over buyers, opportunities can emerge for others.

Bargaining power can be exercised in different ways. We might be talking about negotiations as such, say a large multi-year supply contract or a supply contract for smartphone components. Bargaining power can also be exercised indirectly through purchase decisions of end customers, i.e buying from the lowest-priced company, deferring the purchase for a prolonged period, buying pre-owned (e.g. car) or not purchasing at all.

When you read the below, remember we are not just talking about end-buyers (=consumers). Apple is a seller to the end customers but they are also a buyer of components, such as displays, graphic processing units (GPUs), system on a chip (SoC). They are also a buyer of the assembly services of huge companies like Foxconn who are producing about 40% of all electronics world-wide and employ 1.3 million employees. Here is an image of Apple’ supply chain.

Factors that influence buyer bargaining power:

Seller’s (supplier’s) switching costs: Switching costs can affect both sides, suppliers and customers (=buyers). Customer switch costs are more prominent (explaining this below). Buyers have more leverage where suppliers face switching costs

Manufacturers can face switching costs for upgrades of their productive assets to produce higher quality or higher performance outputs (e.g. steel, fuels, other commodities, electronic components, etc). Say they decide to not undertake one such upgrade as they don’t anticipate sufficient return. If the market moves on they may find having to discount their lower performance or quality products more than they had anticipated

Suppliers will generally pass their switch costs onto the buyer in the long run but economies of scale play a big role in this discussion as low scale will require higher unit cost increases (or longer amortisation times and profit compression)

Interesting questions arise when regulations stipulate higher safety or environmental standards (often giving a multi-year switch window). Who will pay for this? The customer or the seller? Who in the short and who in the long run? Some sellers may switch immediately so they can use it for advertising reasons or offer it as optional (payable) component in the early days

Differentiation of products

Where products are not differentiated (i.e. all competing products have pretty much the same value proposition), competition will be all about the price. Buyers will have the upper hand in particular where there are many competing products

In an undifferentiated product category with many alternates, incremental product upgrades/evolution may be mostly captured by customers without the ability to increase margins considerably

Buyer information availability:

The buyer may not have enough info to make good cost-benefit trade-offs. Products can be opaque or complex (insurance anyone?)

This can lead to the company with the biggest marketing spend exert power over the customer

Comparison and review pages, on the other hand, can erode this power somewhat (but these channels sometimes lose their independence as well)

Platform business models can help reduce search costs

Power of distribution channels:

Large retailers, such as Amazon, Walmart) have enormous power over their suppliers

Apple opened their own stores (online and brick-and-mortar) to reduce their retailer’s power. They now dictate the terms (prices and maximum discounts) that normal retailers have to sign up to if they want to sell Apple products

Apple also is a distribution channel for music (Apple Music) and apps (App Store) and commands considerable margins over the suppliers (artists, labels, app developers) and is fighting court battles over these margins

Network effects can be powerful: switching away from Facebook costs you your network of friends and your photo/video gallery, etc (but multi-homing comes with low barriers, e.g. using Snapchat and Facebook at the same time). Platform business models build competitive (and bargaining) power through indirect network effects

Bargaining leverage, particularly in industries with high fixed costs

Industries with high fixed costs (e.g. hotels, airlines) need to maximise revenue to contribute to their high fixed costs. This erodes their bargaining power esp if the industry has over-capacities and little differentiation

Some other factors are:

Buyer price sensitivity (or demand elasticity)

Fragmentation of suppliers

Discretionary vs staples

Share of wallet

Recency and frequency of purchase

Access to limited resources: airport slots, top ad slots in Google

Our Flagship Course

(2) Bargaining Power of Suppliers

Where suppliers are powerful they may make a larger profit margin than the company that integrates the inputs of several suppliers to sell to the end customer.

And there are cases where suppliers also sell directly to the end user as well as to another company. Samsung sell displays and other smartphone components to competitors as Apple (e.g. iPhone X’s OLED display) and use them in their own phones to sell to the end customer. Hotels sell their room directly to travellers and in some cases they wholesale rooms to the likes of Expedia at discounted rates.

A particularly successful supplier combination was the Microsoft, Intel duo in the PC space. Though many suppliers were involved in a typical PC, the biggest profit margins ended up in these two vendors' pockets when looking over the long run. Other vendors made good profits over certain periods but none of them anywhere close to “Wintel” if you look over the last 3 decades, many component manufacturers went out of business as newer technologies leapfrogged theirs (refer to supplier switching costs above).

Important factors that give suppliers bargaining/pricing power:

Customer’s switching barriers:

The classic examples for high switching costs are: inkjet printers, game consoles, pod coffee machines in the end-user space. But there are many more types of switching barriers, with Microsoft Windows leveraging several of them

More modern examples are smartphones. Switch from Android to Apple (or vice versa) and you will lose some of your apps and data, photos, etc or face large efforts to migrate things across. Some apps make it easy to use them on two different OSs at the same time but they make it difficult to export your data so you can switch away from the app itself. Other apps have proprietary data formats

Apple’s switching cost from one component vendor to another may be considered high, but they are a one-off cost of design and integration and are low on a unit cost basis given large volumes

Apple make strategic choices to source certain components from two different vendors in parallel

and they switch, where useful, between component vendors from one phone generation to the next

And they have insourced their chips in some cases

all of which limits the power of their suppliers

Data migration in enterprise level software combined with a number of other factors, such as training etc can lead to companies delay switching to more modern software for a long time

Microsoft has been found to build anti competitive switching barriers

Patent and industry standards

Owning patents that are part of the industry standard can make a very lucrative business

Qualcomm is a company that has powerful patent portfolio in the mobile communication space some of which are essential for fast mobile data transfer

And they make more revenue from their licencing business model than through direct component sales

They enforce their patents and licensing claims vigorously and are involved in a multi-year lawsuit (and counter lawsuit) process with Apple over this

Brand equity

Having a well-known brand can translate into a number of advantages, such as being able to price higher (=brand equity), accounting for additional sales, being associated with a certain value proposition

It can also lead to stronger bargaining power with its own vendors (who doesn’t want to be a vendor for Apple and accept lower-than-usual margins for that ‘privilege’?)

Limited competition:

Where there is one (monopoly, e.g. new pharmaceuticals, rare earth) or few suppliers (oligopoly, e.g. large passenger aircraft manufacturers)

Many airports are quasi-local monopolies with steep barriers of entry

Supplier vs buyer concentration:

There are millions of fragmented crude oil buyers. And while the supply side is also fragmented they can coordinate themselves better on state and OPEC level. OPEC plus a number of other oil producers (esp Russia) have cut supplies and brought inventories down and prices up (though not quite where they would want it thanks to the US shale oil with the latter being a great example for the threat of new entrants). But clearly, the supply side can coordinate better when there is higher concentration

The airline industry had significant over-capacities and despite being higher concentrated than buyers had abysmal profits on industry-level. Though the buyers are not concentrated, their power is being aggregated by the global distribution systems (GDS) and the online travel agencies. They concentrate bargaining power through providing comparisons in prices. These are important (but by far not the only contributors) for airfares decreasing

Strength of distribution channels:

In some countries, a few large retailers (Walmart, Amazon) have huge leverage over their suppliers due to their scale

Shelf space in those large retailers is considered a valuable and scarce resource which they use to negotiate good terms for themselves with sellers

Online travel agencies have considerable power and can charge commissions as high as 20-30% per sold room

Organisation of labour: labour is an important input. In some countries and industries labour unions are (still) powerful (though it seems to be eroding a lot)

After sales:

The seller may uphold warranties only under a prescriptive service or maintenance regime which may need to be sourced through the seller or authorised providers

Extensions / upgrades / diagnostic capabilities to existing customised systems may have a limited supplier base or require in-depth knowledge that only the OEM has

Other factors:

Dependency on the product: pharmaceutical companies, esp in the patent protection period, can dictate prices

Or more broadly services/goods with inelastic demand (in the short run): fuel, cigarettes, coffee

Buyer is not price sensitive, e.g. luxury products, recreational drugs

Goods/services not frequently purchased or low share of wallet (herbs, salt, etc)

Loyalty programs

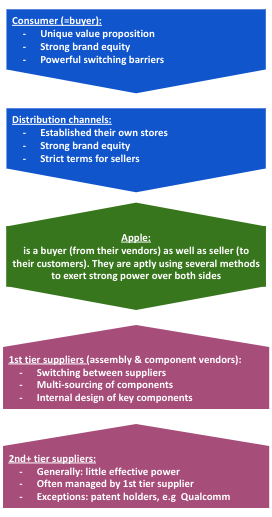

Some ways that Apple uses to exert power over their supply side as well as their buyers

(3) Threat of New Entrants

Winners attract others that wish to get a share of their success. A company that makes above industry-average profits will face the risk of new entrants that may either imitate bluntly or come up with similar (or even somewhat better) value proposals. This threat alone can keep a lid on the achievable profits. It may lead to having into continually add to the original value proposal with limited ability to increase prices.

New entrants will add new capacity, thus supply, to the market which will reduce prices (at least in the medium term). The pace at which competition can form depends on a number of factors listed below.

Barriers to entry: Barriers to entry are economic costs that entrants pay which incumbents do not have to pay (nor had to pay). This is an important concept in economics, strategy and competition law. Having to work around patents or established (exclusive or restrictive) supplier or distribution agreements are just a few factors. Things like high start-up capital, learning curves, etc are not seen as barriers to entry from the theoretical definition of this term. From a practical perspective, they do play a role. You can easily imagine that late movers may find it much more difficult to raise capital when there are already a few strong established players. Michael Porter points out the importance of exit barriers in combination with barriers to entry.

These markets combine the attributes:

“Markets with high entry barriers have few players and thus high profit margins.

Markets with low entry barriers have lots of players and thus low profit margins.

Markets with high exit barriers are unstable and not self-regulated, so the profit margins fluctuate very much over time.

Markets with a low exit barrier are stable and self-regulated, so the profit margins do not fluctuate much over time.

Examples:

High barrier to entry and high exit barrier (for example, telecommunications, energy)

High barrier to entry and low exit barrier (for example, consulting, education)

Low barrier to entry and high exit barrier (for example, hotels, ironworks)

Low barrier to entry and low exit barrier (for example, retail, electronic commerce)”

Here is an in-depth discussion on the US vs Microsoft case (pdf) and pro and cons on barriers to entry

Monsanto is a company getting lots of attention from competition watchdogs

Economies of scale: as scale goes up unit costs go down. This is another micro economic concept that holds true for most firms. Thus, incumbents can achieve higher profits as they have already achieved lower unit costs whereas new entrants have to get to the scale where their unit costs are comparable. Up to that point, they may not be able to have as low prices or have lower profits (thus less cash for further growth)

Industry profitability: The higher industry-profits relative to other industries or the higher the profits of the incumbent relative to the industry, the higher are incentives for new entrants (and capital more accessible) and vice versa

Powers of incumbents: here are some dimensions which we have already explained where incumbents may already be ahead (which may deter entrants):

Network effects

Customer switching costs

Brand equity

Patents

Customer loyalty

Product differentiation

Expected retaliatory actions

As incumbents are further down the unit cost curve and likely more cashed up they can reduce prices when new competition emerges to make it hard for them (though there are limits posed by competition law in many countries). There can be all sorts of other retaliatory action

After sales markets

Many maintenance and asset management plans for capital assets (major plant components, generators, turbines, engines, vehicles or even cars) require access to the data and the ability (intellectual property) to analyse and interpret it in value-adding ways. Even where the data is documented, the IP to analyse often resides with the OEM who either has their own service arm or licensed (for a fee/royalties) service vendors

Other

Government policy – to incentive or disincentive (e.g. through ignorance of market inefficiencies or lobbying by the incumbent) new entrants

Access to key suppliers (key input commodities), resources (e.g. airport slots) or distribution channels

(4) Threat of Substitute Products or Services

Let’s first clarify what a substitute is (and what it’s not). It is not the same product from a different company. Buying petrol from a different brand petrol station is not a substitute. Driving an electric vehicle is a substitute for using oil (it’s a substitute on the dimension of energy but not one on the dimension of transport). Using a train to commute to work is a substitute for using a car (on the transport dimension/industry).

Substitutes satisfy the same basic/economic need (or utility) using a different technology (in a narrower viewpoint coming from the same industry). Clayton Christensen’s concept of “getting the job done” extends this definition. E.g. there are many things that compete for your recreational time which may be suitable to substitute for each other. In this case, the substitutes may be coming from an entirely different industry.

Factors affecting the threat of substitutes:

Price-performance comparison: in both an industrial substitute scenario as well as a consumer scenario price-performance trade-offs matter

How much time does driving to work save you compared to using public transport or UberPool? And how much are you paying more (per trip and per month/year?). How will the price-performance trade-off shift, e.g. traffic speed slowing down due to increased population (permanent factors) or roadworks (temporary factors)? How much would the trip cost need to increase (e.g. due to fuel price increases)? The key is that for different people the thresholds look different.

How much further does traffic need to slow down before more people switch to share bikes, share cars, ride-hailing or alternate private transport solutions? These are essential questions for companies like Zipcar, Uber, Ofo in the decision which cities to enter

As smartphone cameras become better they start becoming a substitute for high-end digital cameras for an increasing amount of people (though surely not for professionals) but more for ambitious amateurs. High-end digital cameras started substituting for professional filming equipment

Buyer’s switching costs (see above) affects the price-performance trade-off as it adds an additional cost to the buyer’s cost of the substitute

For both industrial buyers and consumers high switching costs can prevent or delay switching to substitutes

The efforts involved (ease of substitution) and other factors can translate into actual or perceived additional costs of the substitute

Purchase factors for consumers:

Discretionary vs staples

Share of wallet

Recency and frequency of purchase

Product differentiation: the more a product is differentiated and has unique value propositions, the more difficult it is to find substitutes and to make a price-performance trade-off and thus to switch

Number of substitute products available on the market

Developing a simpler substitute that scores better on the price-performance trade-off can be a great starting point for innovators. This is particularly true if you are looking to develop a substitute for high-profit industries or where products have outstripped the user’s typical requirements.

(5) Rivalry Among Existing Competitors

Not all industries are equal. Some are much more competitive than others. Prof Porter has identified the settings that frequently lead to fierce competition.

Ingredients of highly competitive industries are:

Many competitors of similar size in the industry (i.e. level of fragmentation / low degree of concentration within the industry) can lead to prolonged competition with most innovations being harvested by buyers/consumers. Industries with only a few competitors of similar size can lead to oligopolies

Slow aggregate industry growth (on the demand side) can lead to rivals competing for market share as the “only” way to grow thereby instigating a nil-sum game where everybody tries to get market share from someone else

High fixed costs, i.e. where idle capacities come at high cost leading to pressure to sell at low margins to generate revenue contribution to the cost base

High exit barriers (see above) where the productive assets remain in the market due to their high remaining values

Highly committed players, e.g. industries of national interest (airlines) or prestige (smartphones)

Where competitors have different goals or ways of measuring success. Chinese heavy industries, e.g. steel, have been supported by their government for their strategic importance in urbanisation. Their excess capacities used as exports were large enough to subdue world steel prices. Amazon is measuring financial success differently to its competitors, funding their growth through razor-thin margins, best summarised in Jeff Bezos’ quote “Your margin is my opportunity”

Part 2: Porter's 5 Forces example Uber

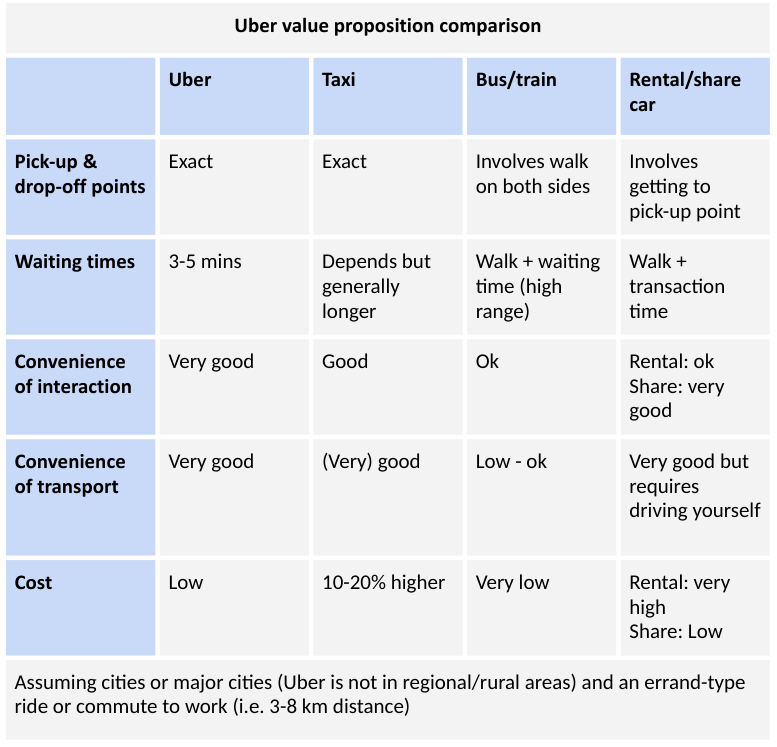

Let’s start with a brief recap of Uber’s value proposition in comparison to its rivals. This plays a role in a number of the forces.

Uber’s value proposition is distinctly different to other forms of transport (=substitutes – force 3) but very similar to other ride-hailing companies (=competitors – force 5)

(1) Bargaining Power of Buyers (=riders)

Bargaining power of customers: on aggregate reasonably high at this stage as there is strong ride-hailing competition, alternate means of transports, taxis and high car ownership. Beyond a certain market share, Uber may have a better pricing position. On certain routes (e.g. airport - CBD) and popular late weekend night routes, the bargaining power of customers is lower

Switching barriers for the demand side: are low. Similar to the drivers, customers are multi-homing. But this may change if the industry ends up becoming a winner-takes-(almost)-all. Due to the indirect network effects, waiting times would increase for competing platforms

Value proposition for customers: are compelling. Lower transaction and search costs, shorter waiting times and lower costs. This is in comparison to other means of transport. But in comparison to other ride-hailing companies there is very little differentiation, thus price will play a big role (as their brand value increases, so can their pricing power)

Buyer information availability: high. Those people who know about Uber also know Lyft and other ride-hailing companies (provided they choose to compare)

Power of distribution channels: low. In this case, we are talking about the app and all competing apps can be equally easily installed. All competing ride-hailing can be used equally easily. If Uber becomes the dominant player due to their network effects, then they become the predominant distribution channel for all (or the majority) of hailed rides, amplifying their advantage. (App stores as a distribution channel for ride-hailing apps are not a consideration in this equation as there are no differences)

(2) Bargaining Power of Suppliers (=drivers)

Bargaining power of supply side: is weak at this stage as there is no unionisation, something that Uber is closely monitoring. We have not yet seen elasticity data for the supply side, i.e. how much higher would hourly rates need to be to attract X number of new drivers? A concept by professor Judy Chevalier in an Uber study, called “reservation wage,” though is a good starting point. But there is lots of discussion in the public space of Uber underpaying drivers (Uber of course states the opposite). This public perception may strengthen the bargaining power of drivers, esp if they are to be considered as employees and receive entitlements. As you know, this is an evolving space.

Switching costs of the supply side: are low. Some drivers are multi-homing by driving for Uber and Lyft (or other ride-hailing companies) at different times. But given hourly wages are similar (and there is no reported shortage of drivers), there is no significant bargaining power gain for drivers at this stage

Value proposition for supply side: compelling. Due to the indirect network effects and the scale that Uber has reached in some cities, they can offer low idle times which lead to comparable per hour wages as taxi drivers but in less absolute time on the street. This may also increase switching costs for drivers, if Uber takes a larger market share. Uber also claims that earnings have improved through UberEats

Barriers to entry for the supply side: It is easy to join Uber and other ride-hailing companies as a driver. But the lower switching costs make it easier for new drivers to join (no multi-year apprenticeship, certificates, etc) effectively reducing the bargaining power of the supply side and – interestingly – increasing the value proposition for new joiners at the same time

The bargaining power of drivers is low but likely rising: Slowly things have improved for drivers over the last 5 years. While one cant extrapolate from this that things will always get better, it seems still probable that the bargaining power of drivers improves (slowly)

(3) Threat of new entrants

Barriers to entry:

On the surface, they are low. Anyone can program an app. But will you be able to scale it up?

Any new entrant needs to get to critical mass. This is often costly in terms of acquiring the supply side and the demand side

Uber has spent billions on demand generation. Customer acquisition costs are very high as seen in the battle with Didi. Will investors be willing to fork out capital for a new entrant to fight an already established brand like Uber?

Will a new entrant be able to get to critical mass on the driver side to provide a comparable value proposition (e.g. low waiting times)?

Could new entrants come from unexpected areas? Maybe Apple, Microsoft, Ford, Toyota, Volkswagen or other companies that already have a huge customer bases and a brand who can mobilise them at low marginal costs? Possible, but Uber is moving into many adjacent/complementary areas, such as freight, meal delivery that may lead to better asset utilisation which other players may not want (or be able) to enter.

Economies of scale:

Can Uber scale up in a way that they have lower unit costs that makes it very hard for new entrants? The answer likely is yes

Can this help Uber increase their lead? Same drivers could work for UberEATS or other conceivable ideas (“the Uber of X”)

If they are able to negotiate better terms for operational, maintenance and servicing for their drivers, this is something that can bring unit cost further down

Some of the economies of scale will pertain even with driverless cars (and most importantly the indirect network effects)

Brand equity: while tarnished temporarily, it is still a major asset and in the long-term

Expected retaliatory action: no doubt, Uber will fight hard against new entrants as they have fought hard in the cities they have entered. This will discourage investors to support new entrants in markets where Uber is strong (mainly the US)

The most likely scenario here is not that another global Uber emerges but rather several local competitors. A lot of locally-focused entrants (possibly with slightly differing value propositions) may dilute Uber’s strength (i.e. financial resources) enough to capture enough market share in those regions

(4) Threat of substitutes

Car sharing companies such as Zipcar

Self-driving cars: many people debate what self-driving cars will mean for the entire transport industry. We are not going to join this speculation. As you certainly know, Uber is investing a lot in self-driving technology themselves

Better public transport: seems very unlikely. We have not heard of any large cities with any success stories on this front (sadly)

More people working from home: it is hard to assess if mobility requirements will reduce due to technological penetration but worth keeping an eye on

Bike sharing can become a better option in cities that are growing fast and traffic congestion becomes an issue

The threat of substitutes is low due to the very different value proposition of the substitutes – check the map above.

(5) Rivalry among competitors

Rivalry is stiff. Though there is no as large player if you look globally, there are many strong players in various geographies:

Ola in India,

Didi has managed to fend Uber off in China,

Lyft is now concentrating its resources to the US

Other competitors are emerging in various locations

A lot of locally-focused entrants may dilute Uber’s strength (i.e. financial resources) enough to capture enough market share in those regions

It is likely that the competition will have to be taken very serious by Uber and it may keep a cap on prices and possibly even on Uber’s pace of growth

Uber itself is expanding into several adjacent areas, such as freight, food delivery, self-driving cars and some other. There are complementary, i.e. synergetic, effects that can increase Uber’s competitive moat